When Robert Francis Prevost appeared on the loggia of St Peter’s Basilica as Pope Leo XIV, he set three precedents.

He is the first pope from North America, the first Augustinian to occupy the throne of Peter, and the first native English-speaker to do so since Adrian IV in the 12th century.

Pope Leo XIV greeted Rome and the world with a simple benediction: “peace be with all of you”.

In choosing a blessing that stressed concord – and in issuing it in Italian and Spanish – he signalled both pastoral directness and cultural breadth.

A Chicago childhood and academic rigour

Prevost was born in Chicago in 1955.

Raised in the working-class suburb of Dolton, he served as an altar boy and attended St Augustine Seminary High School. He studied a bachelor of science at Villanova University, and earned a doctoral degree in canon law at the Angelicum in Rome.

Prevost entered the Augustinian order in 1977, professed solemn vows in 1981 and was ordained in 1982.

For Augustinians, virtue lies not in poverty for its own sake, but in the radical sharing of goods: community precedes individual achievement.

There are three pillars: interiority, the practical love of neighbour, and a relentless search for truth. This framework would guide Prevost’s missionary work, and his call for unity and peace.

Prevost has administered communities in more than 50 countries, but he first arrived as a missionary in northern Peru in 1985. Over the next decade he taught canon law, ran a seminary in Trujillo, judged marriage cases and led a fledgling parish on Lima’s urban fringe.

The experience sharpened his awareness of informal employment, extractive industries and migration – concerns that echo the Rerum novarum , an open letter issued by his namesake Leo XIII in 1891. They remain visible in Prevost’s social priorities today.

In 2015, he was appointed Bishop of Chiclayo, Peru, and, in 2023, prefect of the Dicastery for Bishops, effectively placing him in charge of vetting episcopal appointments world-wide.

What’s in a name?

Created cardinal in September 2023 and elevated to the rank of cardinal-bishop of Albano in February 2025, Prevost entered the conclave with a reputation for quiet competence, linguistic dexterity (he speaks five languages fluently) and unspectacular holiness.

The electors turned to him on the fourth ballot. An hour later he greeted the city and the world as Pope Leo XIV, first in Italian then in Spanish: a bilingual gesture honouring his Italian American Chicago roots and his Peruvian citizenship.

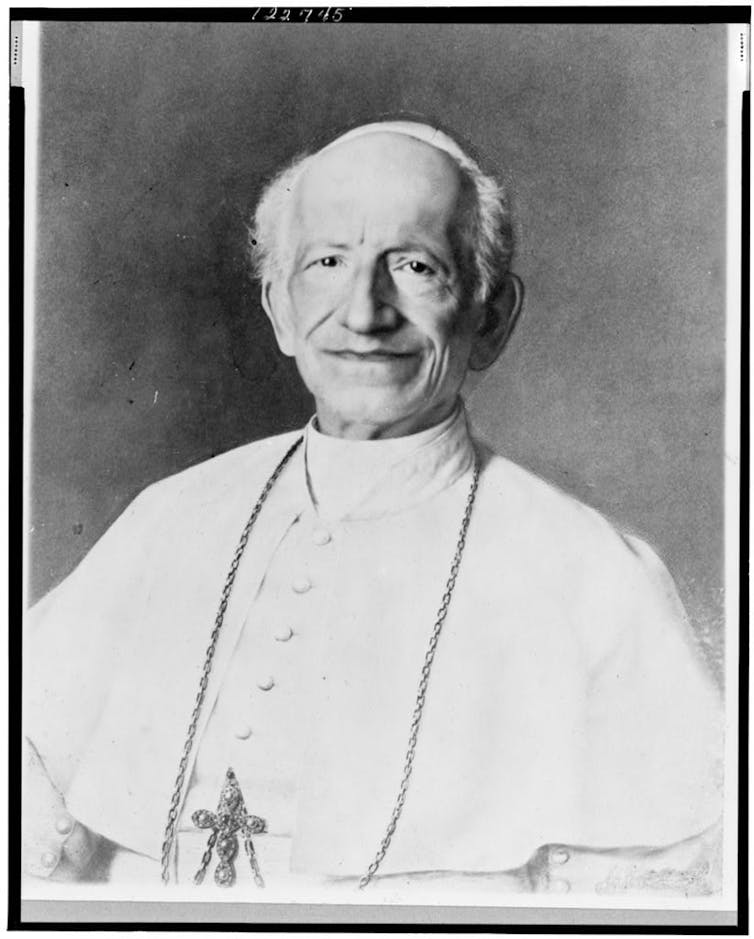

Leo XIV’s choice of name is a programmatic signal. By invoking examples of Rome’s protector Leo the Great (pope from 440–61) and the great social teacher Leo XIII (1878–1903), the new Pontiff intimates he will draw upon their precedent.

His substantive focus will remain squarely on the challenges of 2025: translating Augustinian communal spirituality into governance, extending the social teaching inaugurated by Leo XIII, and mediating polarised factions.

The memory of his Leo predecessors functions as a compass rather than a map, orienting a pontificate whose horizon is the digital, migratory and climatic upheavals of the 21st century.

We can expect where Leo the Great entered dialogue, Leo XIV will offer diplomacy. Where Leo XIII defended trade-union rights and attacked exploitative capitalism, Leo XIV must address labour, climate disruption and forced displacement.

If Leo XIII gave Catholicism its first systematic response to industrial modernity, Leo XIV may be tasked with articulating an Augustinian vision for the digital Anthropocene: a view of humanity as a pilgrim community, bound by shared love rather than algorithmic preference-profiling.

Of one heart

The opening sentence of the Rule of Saint Augustine is “be of one mind and heart on the way to God”.

The order’s stress on interior prayer rather than external activism complements Leo XIV’s preference for silent Eucharistic adoration over elaborate ceremony. The Augustinian tradition of learning aligns with his own scholarly instinct.

Consistent with Francis, Leo XIV has condemned abortion and euthanasia. He has criticised hard-line immigration policies in the United States. He holds the line only men can be deacons. In a 2012 address, he pointed to media normalisation of “alternative families comprised of same-sex partners”.

The combination marks him as a centrist prepared to defend doctrinal boundaries while pressing assertively on social justice, climate action and the governance transparency that Francis began but did not finish.

Challenges ahead

Leo XIV inherits a fragmented Church. Traditionalists fear doctrinal drift, while progressives want accelerated reform of governance, liturgy and the role of women.

His Augustinian commitment to shared discernment could provide a mediating structure. Meanwhile geopolitical crises demand renewed Holy See diplomacy and Vatican finances still run unsustainable deficits.

Ultimately, Leo XIV embodies a living dialogue between tradition and modernity.

Whether he succeeds will depend on his capacity to translate the Augustinian Order’s ancient ideal of one heart, one mind into structures that protect the vulnerable worker, the displaced migrant and the wounded planet.

Yet his formation, intellect and record of bridge-building suggest he understands the Church’s credibility now rests where it did in 1891 under Leo XIII: in that social charity and theological clarity are not rivals, but partners on the road to God.

Like Leo XIII, Leo XIV approaches the world not as an enemy to be refuted but as a moral terrain to be cultivated. His pontificate must confront the ecological, technological and migratory questions of our age.

His inaugural plea for peace hints at an integral vision in which social justice, ecological stewardship and human fraternity intersect.

Whether he can translate that vision into institutional reform and global moral leadership remains to be seen.

By invoking the heritage of Leo XIII, Leo XIV has set the compass of his papacy. It points toward a Church intellectually serious, socially committed and pastorally close: one speaking anew to workers in Amazon warehouses, migrants in detention camps, students in schools, refugees in the Sahel and young people navigating the gig economy.

If he succeeds, the name he chose will read as prophetic promise, linking 1891’s clarion call for justice with the uncharted demands of 2025 and beyond.

Darius von Guttner Sporzynski, Historian, Australian Catholic University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.