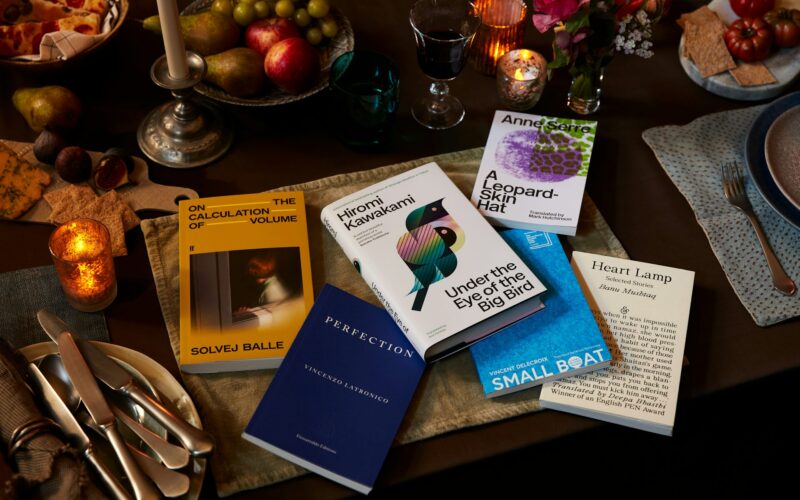

From a longlist of 13, six novels have been shortlisted for the 2025 International Booker prize. Our academics review the finalists ahead of the announcement of the winner on May 20.

Under the Eye of the Big Bird by Hiromi Kawakami, translated by Asa Yoneda

Hiromi Kawakami’s Under the Eye of the Big Bird offers us glimpses of one imagined future for earth and humanity.

Its vision could be described as post-apocalyptic. After unspecified cataclysmic events, humans exist only in tiny, scattered communities and extinction seems imminent. But this is also a beautiful, if dreamlike, world and one in which humanity still has the potential for astonishing growth and change.

Each chapter introduces something new and startling to the reader. Many of the tropes are familiar – cloning, superpowers, mutation, AI. Yet they are configured in unfamiliar ways and prompt reflections on the nature of humanity and our relationship with the rest of creation – as well as on time, religion and the possibility of an afterlife.

Despite grappling with so many huge questions, Under the Eye of the Big Bird is an accessible and absorbing novel. And, although tragedy is never far away, there remains humour – and hope.

Sarah Annes Brown, Professor of English Literature

Heart Lamp by Banu Mushtaq, translated by Deepa Bhasthi

Banu Mushtaq’s Heart Lamp shines a light on the lives of Muslim women in rural India. In a bold and memorable translation from Kannada by Deepa Bhasthi, this quietly powerful collection of short stories opens up the intimate space of domestic rituals and family tensions.

Mushtaq’s fervent advocacy of women’s rights is evident in the compassion with which she brings to life the women in the stories: from the lack of autonomy suffered by young girls forced into wedlock to the indignity of an older woman obliged to accept her husband taking a second wife or a widow whose son arranges a new marriage for her, the women’s lives are dictated by men.

Heart Lamp is perhaps best summed up in the final story, “Be a Woman Once, O Lord!” Throughout these stories, Mushtaq invites us – and whichever male deity might be listening – to walk in the shoes of women overlooked by an unquestioned patriarchal hierarchy.

Helen Vassallo, Associate Professor of French and Translation

A Leopard-Skin Hat by Anne Serre, translated by Mark Hutchinson

Published in France in 2008 as Un chapeau léopard, A Leopard-Skin Hat is a novel about a friendship spanning 20 years between a woman called Fanny and a man known throughout only as “the Narrator”. He is not, though, the narrator of the novel. Rather, an unknown storyteller tells us how the Narrator sees Fanny gradually lose the fight against madness (the novel’s word) and, in the end, death.

This is a novel about the mystery of other people, about how unknowable others are to us. It explores how we narrate to try to understand people who are not us, but whom we love. What is most extraordinary about Serre’s novel is the way it shows us two friends doing very ordinary things – going out for dinner, going on holiday, walking in the countryside and swimming in lakes – but shows us through this the strangeness and complexity of friendship, love and life.

Leigh Wilson, Professor of English Literature

Perfection by Vincenzo Latronico, translated by Sophie Hughes

Perfection is a slim account of the way that time “disappears” for Anna and Tom, an expat couple living in Berlin as creative freelancers in the 2010s.

Written in homage to Georges Perec’s Things: The Story of the Sixties (1965), the novel opens with an overbearing description of the items in their apartment, moving in and out of the characters’ dissatisfaction with the aesthetic, social, creative, economic and political routes open to them in 120 pages spanning a little over 10 years.

As international elections, the European refugee crises and climate catastrophe dance in and out of their peripheral vision, Anna and Tom find neither satisfaction with their current moment nor successfully imagine a better one. As such, Latronico gently, but with an increasing sense of fatalism, considers the stagnation of a millennial creative class whose views on influence, status, power and happiness remain deeply linked to the “new emotions” of digital mediation.

By Rachel Sykes, Associate Professor in Contemporary Literature and Culture

On The Calculation of Volume I by Solvej Balle, translated by Barbara Haveland

In On The Calculation of Volume, a woman, Tara Selter, finds herself trapped in an endlessly repeating day, November 18. Volume I, the first of seven books, recounts the first 365 days of this time loop, with Tara attempting to make sense of her predicament, to explain it to her husband – who is still bound by the normal rules of time – and to try to fix whatever has initiated this situation.

As the novel continues, it becomes less focused on the novelty of the situation and more on the philosophical questions it raises: the alternate claustrophobia and liberation of replaying the same day; how our friends and partners sometimes feel like they inhabit a different reality; the way in which time pulls things and people apart; of the importance we place in the idea of “tomorrow”.

What’s remarkable about Balle’s novel is how compulsive it is – even though we know time is standing still, we still want to know what will happen next.

David Hering, Senior Lecturer in English Literature

Small Boat by Vincent Delecroix, translated by Helen Stevenson

Vincent Delecroix’s Small Boat is a slim, bruising novel that centres on a real horror: the drowning of 27 migrants in the English Channel in November 2021. In a small, inflatable craft, they reached out over crackling radio lines, asking for help that never came.

Small Boat focuses not on the migrants themselves, but on a French coastguard operator who spent that night on the radio, fielding their calls for rescue. Delecroix’s brilliance lies in showing how violence at the border is carried out not by villains, but by workers. It was not evil that allowed those people to die in the water, it was a string of decisions made by people in warm rooms who believed they were doing their jobs.

In a world ever more brutal towards those who flee war, hunger and despair, Delecroix’s novel is a necessary – and merciless – indictment. It reminds us that the shipwreck is not theirs alone. It is ours too.

Fiona Murphy, Assistant Professor in Refugee and Intercultural Studies

Helen Vassallo, Associate Professor of French and Translation, University of Exeter; David Hering, Senior Lecturer in English Literature, University of Liverpool; Fiona Murphy, Assistant Professor in Refugee and Intercultural Studies, Dublin City University; Leigh Wilson, Professor of English Literature, University of Westminster; Rachel Sykes, Senior Lecturer in Contemporary Literature, University of Birmingham, and Sarah Annes Brown, Professor of English Literature, Anglia Ruskin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.