In the run-up to Valentine’s Day, Adriana Bishop follows her nose through the winding streets of Florence on a 24-hour whirlwind tour to discover the art of fragrance making in the city of perfume… or “potions of love”.

The heavenly scent hits me right from the doorway. As I step inside the palatial hallway, leaving behind the hustle and bustle of tourist-clogged Florence, I am enveloped by a sense of calm, while the welcoming perfume lures me in towards a great hall with a frescoed vaulted ceiling and a sparkling chandelier.

The palatial salesroom is busy with tourists sniffing vials of perfume, imbued with centuries of history, reflecting Florence’s perfume tradition. Despite the excited murmur of customers, there is a hushed reverence as if we were in a library rather than a perfumery.

Florence’s architectural and artistic gems need no introduction, but on my third visit to the city I was eschewing the famous duomo with its never-ending queues and the masterpieces at the Uffizi gallery. I was on the trail of another of Florence’s artistic contributions; one even headier than Brunelleschi’s dome – perfume.

The city of the lily and the birthplace of the Renaissance was also once considered to be the perfume capital of Europe. Its 17 historic perfumeries are a testament to a centuries-old tradition that is still going strong today. It was Catherine de Medici, then only 14 years old, who put Florence on the international perfume map when she brought her personal perfumer Renato Bianco with her to the French court in 1533. After changing his name to the more French-sounding René le Florentine, he would go on to open the first ever perfume shop in Paris, developing fragrances mainly as “potions” of love. At the time perfume was often used to hide the smell of leather gloves.

Before leaving Florence to marry Henry II of France, the young Catherine had commissioned the Dominican monks to create a perfume for her. Acqua di Santa Maria Novella, her own special perfume made with bergamot, is still produced today to the same original formula by one of the oldest pharmacies in the world, Officina Profumo Farmaceutica di Santa Maria Novella [www.smnovella.com]. Established in 1221 by the Dominican monks shortly after their arrival in Florence, the pharmacy is my first stop on a fragrant whistle-stop tour of the city.

Still basing its products on the same natural herbs the friars used to cultivate in their gardens for medications, balms and ointments for their convent’s infirmary, the Officina today has a cult following worldwide. Some of its products such as the rose water [first created in 1381 and used as a disinfectant during the plague] and Acqua Antisterica [produced in 1614], made with locally grown costmary, famous for its digestive properties, have been bestsellers since the pharmacy opened to the public in the 1600s.

The shop on via della Scala is also a living museum, with its antique cabinets, painted ceilings and ornate décor reminiscent of the opulence of Florence in its Renaissance heyday. On the occasion of its 400th anniversary, the Officina undertook an extensive restoration of the historic sales rooms, including the sacristy of the chapel of San Nicolò, which is entirely covered in frescoes depicting the passion of the Christ and painted by Mariotto di Nardo between 1385 and 1405.

That introduction into the Florentine world of fragrance was just a prelude to the highlight of my visit as I was booked to learn the secrets [or some of them, at least] of perfume making from a professional “nose”. Tucked away down a side street behind the Bargello Museum and just metres away from its original site on Piazza San Simone, Antica Spezieria Erboristeria San Simone [www.anticaerboristeriasansimone.it] has been creating perfumes since 1700. Its current owner, chemist and herbalist Dr Fernanda Russo, greets us warmly in the small shop surrounded by hundreds of bottles containing myriad essences and oils, but that is only the part we can see as the edifice extends much further beyond two plain curtains where perfumes and creams are made by hand using only natural ingredients.

Originally founded by a gardener and herbalist who used to run the giardino semplice [simple garden] of a local convent, San Simone was run by the ancestors of the Castaldi family for generations from 1700 until 1993. The original herbalist shop in piazza San Simone was called Semplicista after the garden. It stood there for well over 200 years until the devastating flood of 1966 destroyed it. The family re-opened the shop further up the road in its current location on Via Ghibellina, renaming it San Simone in honour of its original site.

Dr Russo took over the shop in 1993 from the last surviving member of the Castaldi family thus taking the San Simone tradition into a new era while respecting its origins.

As I take my place around a 120-year-old table, together with three other American tourists, I look apprehensively at the numerous vials and small bottles spread in front of me. For a moment, I am taken back to my Form 3 chemistry lessons and realise that creating a perfume may have less to do with romance and more to do with chemical affinities. On closer inspection, I notice that the bottles are not randomly placed on the table; rather they follow a pattern which I soon learn is the all-important olfactory pyramid where the head or top notes are the first fleeting hit of fragrance that lasts mere seconds, the middle or heart of the pyramid is the central focus that lingers between two and four hours and is supported by the base notes, the body of the perfume that fixes the fragrance and lasts for up to 16 hours.

It is clear from the moment the workshop begins that, for Dr Russo, perfume is so much more than just her profession. It is her life. “Perfume is my secret island,” she tells me. “For me, perfume is the search for serenity; something that makes me feel good, that appeases the soul; it is everything that makes me feel more confident to face daily life, which is full of challenges.”

As she teaches us how to smell the essences and think about the memories each one evokes, she reminisces about how her passion for perfume started during a childhood punctuated by strong fragrances from the fields, the gardens, the sea, from the kitchens and from her grandmother’s love for roses.

“My passion for perfume goes back a very long time to my childhood and my time spent with my grandma Rosa, who loved roses and anything that smelt of flowers and cleanliness. I remember when we used to take her perfume out of the drawer, open the stopper of the eau de cologne, and before going out, she would spray us with this fresh fragrance of roses. Sometimes, I would accompany her to the field where she would hang up the laundry to dry, ultra-white and very fresh laundry, reminiscent of the heady scent of almond blossom,” says Dr Russo.

“In the afternoons, we would all meet up in the garden of my great aunt where the little girls would play and watch the older women sew or embroider. There was the smell of orange blossom that would always be included in a young bride’s bouquet, and at the right time of year, the intoxicating fragrance of jasmine, so heady and strong. In summer, we would move to the house by the sea where I would spend hours watching its colours, the smell that emanated from it and the sound of the waves crashing on the shore. I also remember the smell of home-baked sweets and homemade jams. My sense of smell was thus honed from a very young age as it was subject to such strong external stimuli,” she explains.

A chemist by profession, she shunned the pharmaceutical industry in favour of creating perfumes and creams using only natural ingredients. But becoming a “nose” is not easy. “This is a multi-faceted profession, a complex mélange of technical and scientific skills, together with an artistic baggage acquired through the discovery of art and its history as well as a deep sensitivity sustained by a strong memory and plenty of willpower that enables you to transform your life experiences into artistic creations,” points out Dr Russo.

We didn’t have years ahead of us to become real “noses”; 90 minutes was all we had to create our own bespoke perfume, but Dr Russo patiently guided us through the rudimentary basics. Before she let us unscrew the essence bottles, she reminded us that “a perfume is like a partner; it accompanies you like a friend; it is a part of your life”. What a comforting thought.

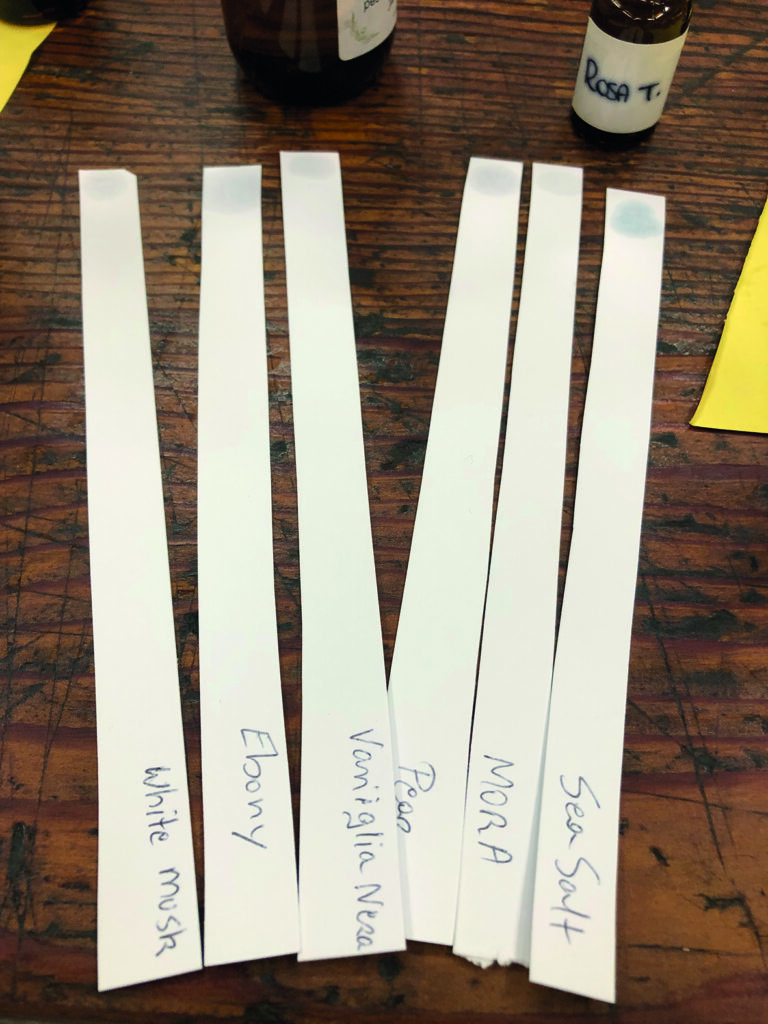

Starting with the base notes, or the foundation of the perfume, we had a selection of woody, musky, animal and resinoid essences, such as white musk, ebony, black vanilla, fig, ambergris and vetiver root. As these fragrance fixers would be the longest lasting smell of the perfume, it was important to choose the right ones. We carefully put a drop of each essence on thin paper strips, which we learn are called mouillettes, and waft them in front of our noses. At first, the experience is simply pleasant, but soon I start to discern how the smells make me feel, which ones make me happy, calm or remind me of positive or negative thoughts. After much smelling and consideration, I finally settle on white musk and ebony.

A cup of coffee granules is offered round, not for making coffee, but to sniff and “clean” the nose from all the fragrant smelling before starting again afresh. We thus move on to the most important part of the perfume – the heart. The base notes need to maintain and support the heart notes of the perfume. The selection here included all the flowers, such as iris, rose, orange blossom, light, fruity ones like pear, lavender, which is classified separately as it is so strong, sweet smelling honey and chocolate, bergamot, talc, woody smells, such as pine, fir, juniper… It was not hard for me to go for rose, also a favourite with Dr Russo.

The top notes are the most volatile, lasting only a few seconds, but they are essential to open up the perfume. These include citrus, aquatic essences, fruit, grass, aromatic herbs, such as basil and verbena. I quickly choose sea salt primarily because its brilliant blue colour reminds me of the sea back home in Malta. I pair it with blackberry.

I finally had five mouillettes representing my own perfume. It smelt fresh, clean, summery and immediately made me dream of beach holidays. Dr Russo worked out exactly how many drops of each essence I needed to create a balanced perfume and I was set to work counting the drops in a little beaker. The perfumed concentrate is then diluted with 95-per-cent-proof alcohol and bottled. My personal perfume was ready. But I now had to wait 15 days before I could open the bottle and start wearing it. Even Dr Russo seems pleased with the results.

We are permitted a tiny drop of our perfumes on our wrists, and as we smell each other’s handiwork, we marvel at how the perfumes reflect our personalities. Dr Russo remarks how perfume choices tend to vary depending on cultural influences.

“These days, there aren’t that many differences between perfumes for men and women, especially as it is often the women who choose the perfume for their partner. However, I do notice a difference in perfume choice depending on which country people come from. The European tourist often chooses citrus-based or fresh-smelling perfumes; Asians such as the Japanese or Chinese choose perfumes that are ‘non-perfumes’, delicate aquatic creations; Russians or Eastern Europeans tend to go for strong florals; while Americans prefer persistent perfumes, which include a lot of vanilla or fresh greens.”

And what would Florence’s perfume be? One word, she replies: Hedonism. “Florence embodies history, art, architecture, philosophy, freedom of thought, medicine, physics, music, traditions and the primary example of all this can be seen in Leonardo da Vinci as well as in Dante Alighieri in his Divine Comedy.”

While Dr Russo laments there are still not enough people training and working as “noses”, creating artisan perfumes, she points out that Florence’s perfume tradition is still strong and is often tied into art exhibitions, fashion, or even gastronomy as a concept that embraces every aspect of life. Every September, Florence stages Pitti Fragranze, a three-day showcase of niche fragrances and associated products displaying the best in artistic perfumery.

With my perfume in my bag and a “certificate” stating I had successfully completed a perfumery course, I continue my fragrant walk through Florence, visiting other perfumeries such as Aquaflor [www.aquaflorexperience.com] housed in the vaulted rooms of an old palazzo in Borgo Santa Croce. This is a perfumery for real connoisseurs with deep pockets. I choose some budget-friendly but nonetheless exquisitely perfumed soaps, which are expensively wrapped, boxed and tied with a ribbon, and I feel like I have walked out of the shop with a piece of history in my bag.

Some perfumeries are hidden behind anonymous doors like Arômantique [www.aromantique.it], a little gem of a place with a magical oasis of a garden tucked inside a plain-looking building down a residential street. Others are sandwiched between the ubiquitous leather shops. All are a joy to discover, if somewhat pricey to indulge in. But then, if a perfume is to be your partner in life, the right one is worth every penny.

In the late afternoon, I cross the Arno and walk up to the Rose Garden beneath Piazzola Michelangelo. As I watch the sun cast its golden glow on the majestic skyline of old Florence, I feel it is a fitting end to my perfumed tour, surrounded by the heart notes of my perfume – the glorious rose.

For a full tour of Florence’s perfumeries, visit www.toscana.artour.it